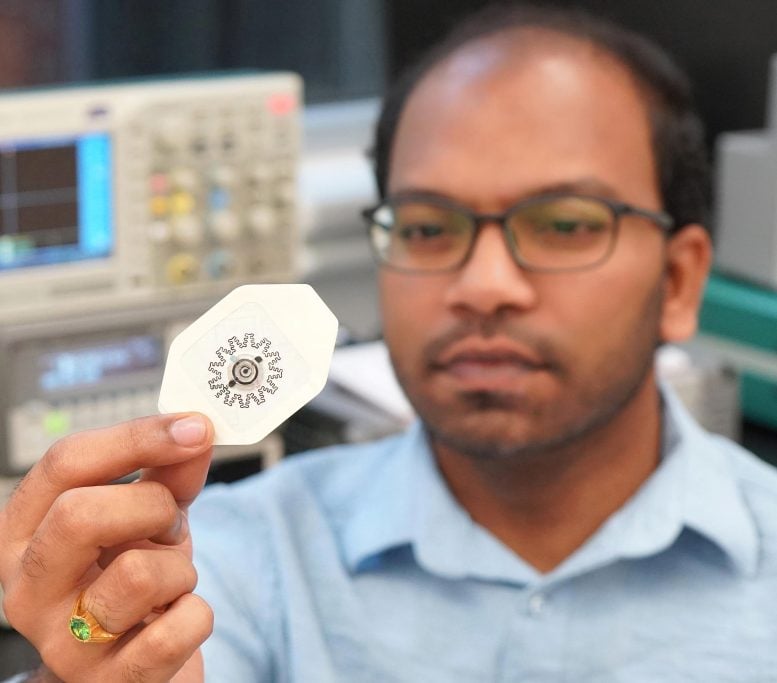

Photo by: Rajaram Kaveti

Among the latest medical technologies is a water-powered, electronics-free dressing (WPED) that provides cheaper and quicker healing of chronic wounds in the comfort of homes, according to a study published in Science Advances.

The technology is the product of a collaborative study supported by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, which seeks to develop emerging tech for military use. However, researchers claimed that WPEDs are meant for general application.

“Our goal here was to develop a far less expensive technology that accelerates healing in patients with chronic wounds. We also wanted to make sure that the technology is easy enough for people to use at home, rather than something that patients can only receive in clinical settings,” stated Amay Bandodkar, co-corresponding author of the study and an assistant professor at North Carolina State University (NC State).

Chronic wounds do not heal within normal time frames, typically after three months. They are often caused by poor blood flow and diabetes and could lead to amputation and death without proper medication. Currently, the available treatment options for chronic wounds are inaccessible to many patients due to their high prices.

Bandodkar and his team want to change that with a WPED, which relies on an electric field powered by water to heal chronic wounds faster than conventional treatments.

The Science Behind

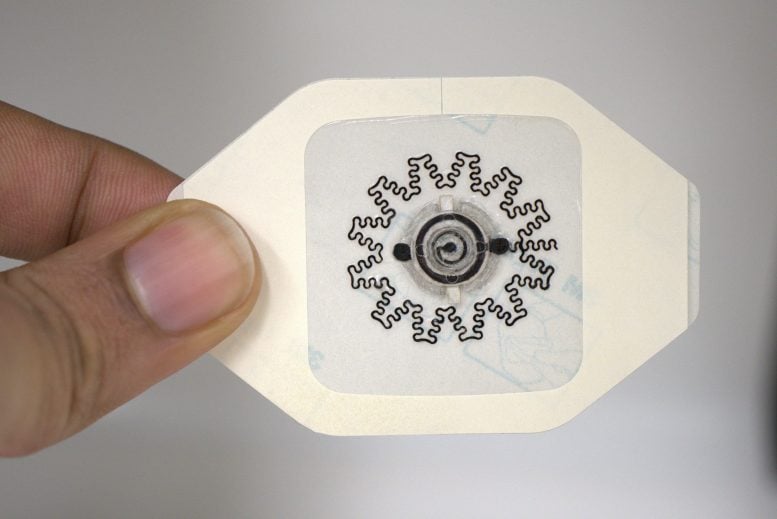

A WPED is a disposable wound dressing composed of electrodes on one side and a tiny, biocompatible battery on the other. When applied, the electrode side is in contact with the wound, while the battery is activated by adding water to produce an electric field for several hours.

“That electric field is critical because it’s well established that electric fields accelerate healing in chronic wounds,” explained NC State researcher Rajaram Kaveti, co-first author of the research.

Kaveti elaborated that the design of the electrodes is also crucial as it allows them to be flexible and conform to the often irregular shape of chronic wounds. Moreover, the ability to conform directs the electric field from the wound’s periphery toward its center.

“In order to focus the electric field effectively, you want electrodes to be in contact with the patient at both the periphery and center of the wound itself. And since these wounds can be asymmetrical and deep, you need to have electrodes that can conform to a wide variety of surface features.”

From Animal Test to Human Application

To determine the efficacy of the wound dressings, they were tested in diabetic mice, which are common models used for human wound healing.

“We found that the electrical stimulation from the device sped up the rate of wound closure, promoted new blood vessel formation, and reduced inflammation, all of which point to overall improved wound healing,” said Maggie Jakus, co-first author of the study.

To be specific, the test revealed that mice who were treated with WPEDs healed 30% faster than those who were treated with conventional bandages.

Following this positive result, the researchers are now looking to improve the technology as it nears clinical trials and practical use for the general population.

“Next steps for us include additional work to fine-tune our ability to reduce fluctuations in the electric field and extend the duration of the field. We are also moving forward with additional testing that will get us closer to clinical trials and—ultimately—practical use that can help people,” Bandodkar noted.